To quote the legendary Pan-African author, Amos Wilson, “If restitution and reparations are not instituted to compensate for prior injustices, those injustices are effectively rewarded…” This statement illustrates the significance of restitution, or efforts to correct historical injustices and provide compensation or reparations, (social) justice, recovery, and accountability.

Since Emmanuel Macron’s remarkable speech to return African treasures to France and his endorsement of the Sarr-Savoy report on restitution, the global discourse about cultural restitution and reparation has taken a different turn now (Fongang et al., 2023). The toll rises by the day as more countries seek restitution as a form of justice and accountability for (colonial) crimes committed in the past, crimes that have stripped them of their national dignity and identity. Max Fisher’s New York Times article states, “Former colonies have felt increasingly empowered to demand compensation from European powers. But even the successful efforts look like exceptions so far” (Fisher 2022). The last part of the statement is very genuine, given that the demands for many reparations and restitutions have been greeted with denials and “legal excuses.” Only a few restitution cases have succeeded, allowing one to hope and believe in the possibility of restitution. There is no rational reason why a country’s heritage should not be restored, especially when the circumstances behind its ownership are deceitful and cruel.

As previously stated, several restitutions are happening around the world today. In this piece, we will discuss five intriguing ongoing restitution instances, highlighting the restitution procedure’s progression in a bid to assess each case.

Cameroon

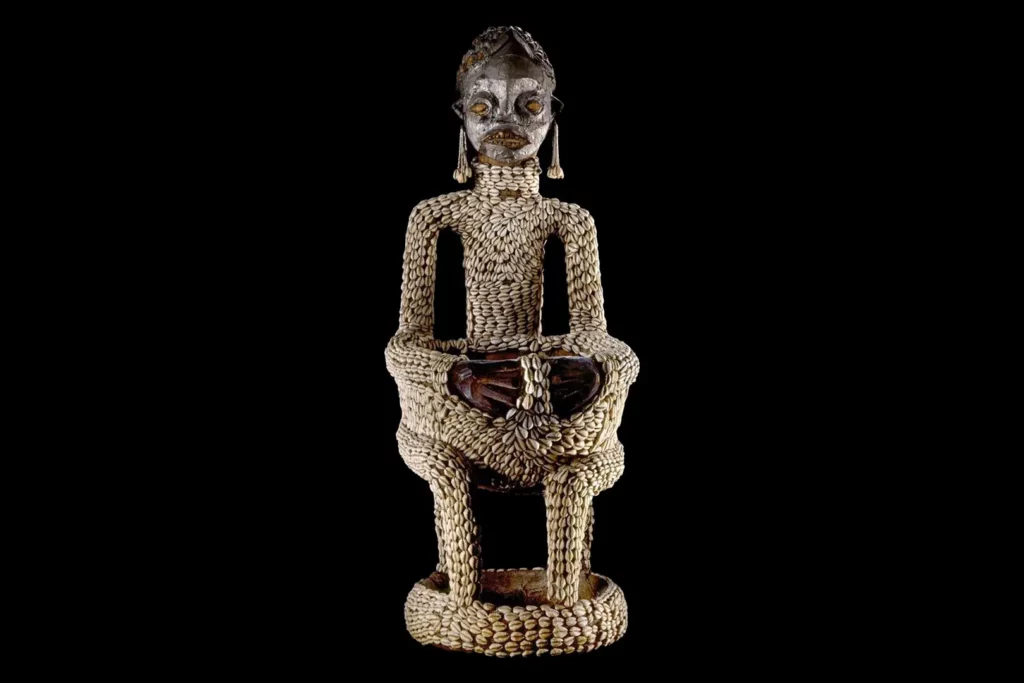

The Ngonnso restitution is Cameroon’s most active and successful case of restitution. The Ngonnso is the progenitor of the Nso clan in Cameroon’s Northwest region, which German soldiers looted from the Nso Royal Palace during colonial times. In 2020, “artivist” Njobati Sylvie began advocating for Germany to return the Ngonnso to the Nso people. In 2021, she also initiated the #BringBackNgonnso Online Campaign, which drew Germany’s attention and resulted in the signing of the agreement to return the Ngonnso in June 2022. Even though a decision has been signed, Ngonnso’s repatriation is still riddled with obstacles. Rumour has claimed that Germany is using the Cameroonian government’s disengagement from the Ngonnso restitution process to delay the actual return of the Ngonnso, referencing the delay of the return of the Ngonnso on Germany’s state-centric approach to restitution. We are pleased to know that this is no longer the case, as the Cameroonian delegation recently visited Germany to discuss the restitution of Cameroonian Cultural Heritage in Germany back to Cameroon.

Photo Credit: Marc Sebastien Elis

Nigeria

Another significant and well-known continuing cultural restitution dispute between Nigeria and a handful of European institutions (Britain, Germany, etc.) is the Benin Bronzes. The Benin Bronzes, like the Ngonnso, were illegally stolen following a brutal British invasion of the West African Kingdom of Benin (present-day Nigeria) in 1897.

Photo Credit: PHOTO DANIEL BOCKWOLDT/PICTURE-ALLIANCE/DPA/AP IMAGES

Nigeria and these European museums are at odds over ownership of the Benin Bronzes. While France and Germany continue to return the treasures, other countries, such as Britain, have maintained a stubborn, hard-headed stance on the return of the bronzes and other artefacts. As is customary, Britain’s opposition is based on stated legal limits, which may be only a ruse for refusing to negotiate or return these African looted legacies.

Ethiopia

Ethiopia did lose numerous cultural and religious legacies to the British explorers after the latter raided the former Maqdala capital of Ethiopia- then known as Abyssinia. After the defeat of Emperor Tewodros II in the 1868 Maqdala battle, the British soldiers looted amongst other treasures: the sacred plaques “tabots” owned by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, the Abyssinia regalia, and the 7-year-old Prince Ahemaleyu. For more than 145 years now, these and other Ethiopian treasures have been stored at the British Museum. Only recently, some of these treasures ( the sacred tabots and a lock of Prince Ahemaleyu’s hair) returned to Ethiopia with the help of private benefactors.

While we appreciate these efforts, we also want to highlight that Britain continues to uphold a negative position on the return of the ancestral remains of the late Prince. Their “excuse” for this shameful response is that they are unwilling to disorganise the other tombs at the medieval Winsdor cemetery, where the Prince was laid after his passing in 1879.

Photo credit: Amanuel Sileshi

Greece

Another sought compensation from the British Museum in exchange for the return of the Parthenon Marbles, popularly known as the Elgin Marbles. Lord Elgin removed these ancient Greek sculptures from the Parthenon in Athens in the nineteenth century, and they are now housed at the British Museum. In a BBC interview, the cultural secretary, Michelle Donelan, reveals that returning the Parthenon sculptures to Athens – to use a not-so-random example – “would open the gateway to the question of the entire contents of our museums.” Could it be that Britain’s denial to return the Parthenon Marbles is because of its high significance amongst all other collections of the British Museum?

Photo Credit: Jeff Overs

Indonesia

The Netherlands keeps approximately 486 treasures looted from Sri Lanka and Indonesia during colonial times. The Netherlands only returned these treasures early this year after a 2020 report by an advisory committee urged the government to unconditionally return looted cultural artefacts if requested by their countries of origin. The Lombok Diamond is an excellent example of the Indonesian legacy that was returned to Indonesia by the Netherlands. The treasure is a 75-carat diamond piece that resided in the Ethnological Museum in Leiden with violence and was forcefully looted by Dutch East Indies soldiers during the Lombok War in 1894.

The case of the Lombok Diamond is just one of the many requests for restitution that Indonesia has requested from the Netherlands. However, a written piece published by the Guardian shockingly reveals that not all of these heritages were returned to Indonesia. The ancestral remains of the Java man and the entire fossil collection of Eugene Dubois, a palaeoanthropologist who excavated about 40,000 fossils from Indonesia during the 19th century, are yet to be returned to Indonesia, which has requested its restitution since 2022.

In conclusion, the issue of restitution cases is complex and multifaceted and extends far beyond any one country’s borders. As we have seen through the points above, the struggle for justice and the return of cultural heritage is an ongoing battle. These cases highlight not only the historical injustices that have been perpetrated but also the deep-rooted cultural significance of these artefacts and the impact their absence has on the communities of origin. The fight for restitution is not just about reclaiming objects; it is about reclaiming identity, heritage, and the right to tell one’s story from one’s perspective. While progress has been made in recent years, it is clear that there is still much work to be done. Governments, institutions (Museums), and individuals must continue collaborating and engaging in dialogue and negotiations to find equitable solutions that prioritise the interests of the communities affected. As we move forward, we must maintain momentum and continue to raise awareness about these restitution cases.

Sources for further reading

- Clara Cassan, Centre for Art Law (2019, January 31). The Sarr-Savoy Report & Restituting Colonial Artifacts. https://itsartlaw.org/2019/01/31/the-sarr-savoy-report-restituting-colonial-artifacts/

- Lauren Sproule; CBC News (2023, September 20). A piece of a 19th-century A Piece of a 19th-century Ethiopian Prince is going home https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/prince-alemayehu-1.6972478;

- Returning Heritage. (2023, September 22). Private benefactors ensure precious artefacts are returned to Ethiopia. https://www.returningheritage.com/private-benefactors-ensure-precious-artefacts-are-returned-to-ethiopia

- Alex Greenberger, The ART Newspaper (2021, April 2). The Benin Bronzes, Explained: Why a Group of Plundered Artworks Continues to Generate Controversy.https://www.artnews.com/feature/benin-bronzes-explained-repatriation-british-museum-humboldt-forum-1234588588/

- Scottish Legal News (2022, October 19). Indonesia demands the Dutch return looted valuables https://www.royalcoster.com/blogs/craftmanship/the-banjarmasin-diamond-gem-with-a-questionable-history

- Katie Razzall. BBC News (2023, January 11). Parthenon Sculptures belong in the UK, says Culture Secretary Michelle Donelan. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-64235854

- Max Fisher, The New York Times (2022, September 1). The Long Road Ahead for Colonial Reparations. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/27/world/americas/colonial-reparations.html

- Ian Sample. The Guardian (2019, December 18). First human ancestors to leave Africa died out in Java, scientists say. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/dec/18/first-human-ancestors-to-leave-africa-died-out-in-java-scientists-say

- Philip Oltermann and Senay Boztas. The Guardian (2023, July 6). Netherlands to return treasures looted from Indonesia and Sri Lanka in colonial era. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jul/06/netherlands-to-return-treasures-looted-from-indonesia-and-sri-lanka-in-colonial-era

- France 24. (2022, February 19). Benin exhibits looted treasures returned by France.https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20220219-benin-exhibits-stolen-treasures-returned-by-france-in-presidential-palace

- Raad Voor Cultuur (n.d) https://www.raadvoorcultuur.nl/documenten/adviezen/2020/10/07/summary-of-report-advisory-committee-on-the-national-policy-framework-for-colonial-collections

- Clément Ndé Fongang, Mario Laarmann, Carla Seemann and Laura Vordermayer (2023). Reparation, Restitution, and the Politics of Memory / Réparation, restitution et les politiques de la mémoire. Saarland University, Saarbrücken, Germany.